David Shribman was a self-described “nervous kid” who grew up in a small beach town in Massachusetts. “I threw up a lot,” admitted David.

David Shribman was a self-described “nervous kid” who grew up in a small beach town in Massachusetts. “I threw up a lot,” admitted David.

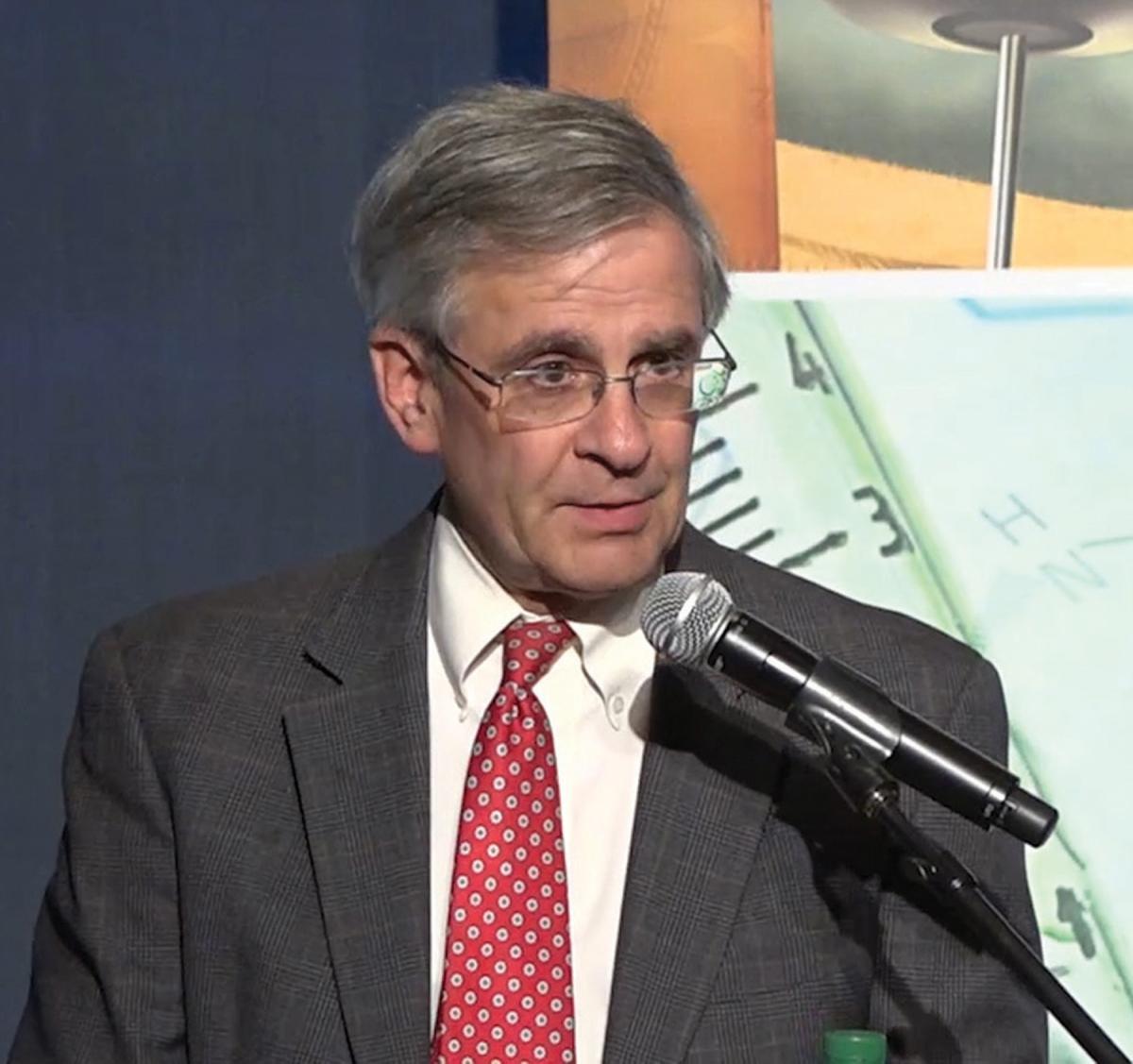

Now-a-days, you are more likely to find David on the dais than anyplace else. “I speak publicly, and usually flawlessly, 12-15 times each month.”

David, a life-long newspaperman, is currently executive editor and vice-president of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, a position that requires many public appearances for speeches, panels, presentations, and other public conversations in front of groups both small and large. He previously worked as a reporter for the Boston Globe, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Star, and The Buffalo Evening News. In 1995, he was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of national politics and the Washington scene.

During his sophomore year of high school, David inexplicably began to stutter. “In high school, my stutter developed and it made me terribly self-conscious,” he said. “I hated the telephone. I thought it was the instrument of the devil. And having a stutter wasn’t the best way to meet girls.”

“I was also the class president and was scared to death of standing at the microphone in front of the class. I had such a hard time talking to a large group of my classmates. I developed a few funny routines to help me get along.” When speaking in public, David used to click his tongue, relax his jaw and even use a little singing to help get his words out. But he remained frustrated and embarrassed. “I was truly mortified,” he added. “I sometimes still click my tongue even today when I speak.”

Through his public high school, he began seeing a speech therapist. She told David to get a book of famous speeches by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, go to the beach, and read them out loud. “So there I stood at Phillips Beach, book in hand, reading FDR’s Four Freedoms speech and his Day of Infamy as the surf crashed along the beach.” David’s experience with stuttering left him with him three valuable lessons:

“First, I came to realize that there wasn’t anything special about reading speeches to the ocean. It was a placebo. But it made me talk and it helped me become more fluent. In that sense, it really worked well. Second, what I learned about FDR by reading his speeches over and over again served me very well in my own writing over the years, covering politics and the White House for various news organizations. And third, I learned to have immense patience for anyone who stutters, and to never, ever finish their sentence,” he said.

“When I covered the 1984 presidential race, I spent hours talking about stuttering with Annie Glenn, and gifted photographer P.F. Bentley, who both stuttered. It gave all three of us a sense of camaraderie, of shared misery to have each other.”

Along the way, David has learned a few things about stuttering. “It’s not a fatal disease. It’s endurable and conquerable. It measures one’s courage and character,” David added.

Despite a life of professional fulfillment, David counts his ability now to stand comfortably in front of large audiences among his greatest achievements. “That’s not something I could have imagined when I was 15 years old. I would have bet it more likely that I’d be hit by a meteor than end up on stage a couple of times each week speaking into a microphone.”

From the Summer 2016 Newsletter

Podcast

Podcast Sign Up

Sign Up Virtual Learning

Virtual Learning Online CEUs

Online CEUs Streaming Video Library

Streaming Video Library