Researchers have linked a newly discovered gene to persistent stuttering into adulthood, giving hope to those with severe speech disorders.

By Professor Michael Hildebrand, Austin Health and the University of Melbourne, and Professor Angela Morgan, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and the University of Melbourne

Stuttering is a common speech disorder that interrupts speech fluency and tends to cluster in families.

|

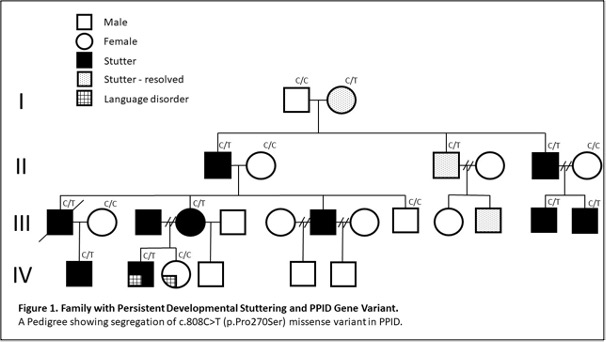

| Family with Persistent Developmental stuttering and PPID Gene Variant. A Pedigree showing segregation of c.808C>T (p.Pro270Ser) missense variant in PPID. |

Researchers have identified many genes that influence other severe speech disorders, like apraxia of speech and dysarthria, including through our programs at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute’s Speech & Language Research Program and the NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence Translational Centre for Speech Disorders.

But despite over 20 years of research, the genetic architecture of stuttering remains poorly understood. Only four genes that cause stuttering have been identified to date. This is very different to other neurodevelopmental conditions where tens to hundreds of genes have been identified.

Our large team of researchers, led by the University of Melbourne in collaboration with 17 international institutions, has discovered a link between a newly discovered gene pathway and structural brain anomalies in some people who stutter into adulthood, opening up promising research avenues to enhance the understanding of persistent developmental stuttering.

|

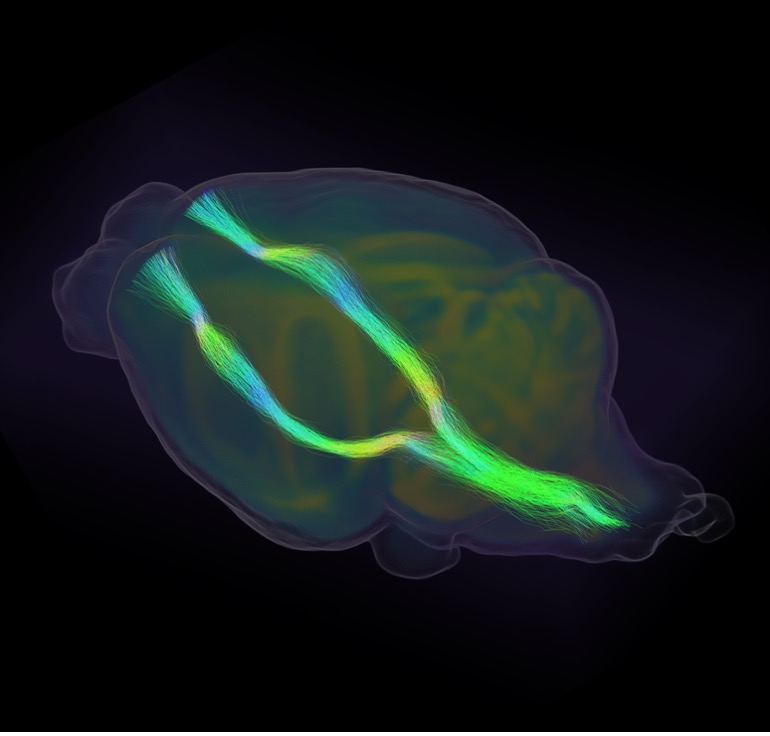

| Brain Imaging of Mouse Model with the Same PPID Gene Variant as the Family. Bird’s eye view of a mouse brain with the corticospinal tracts highlighted. The tracts are white matter bundles that connect the spinal cord (not shown) to the motor cortex and have developed abnormally due to the PPID variant. |

In research published in the journal Brain, we studied 27 members of a four-generation Australian family; ten members of this family have stuttering and three used to have stuttering but this was resolved in adulthood after therapy.

Using brain imaging we found remarkable structural changes in the brains of those that stutter, that impact their speech and language development.

We also found a variant of a newly discovered gene called PPID in the family members with severe developmental stuttering. PPID codes for a chaperone protein, and so for the first time we have a link between stuttering and a ‘chaperone pathway.’

Chaperones are proteins that shuttle other proteins to the correct part of a cell so they can complete their function. We suspect the damaged PPID gene changes the movement and function of various proteins during brain development, triggering neural changes that cause persistent stuttering.

To test this, we generated a mouse model with the same gene defect, and the mice developed structural changes in similar brain regions to those of the family members with stuttering. This includes abnormalities of the corticospinal tracts which support speech and language development.

We have known for some time that there is a genetic link to stuttering, but this study is the first to show that genetic changes passed on in families can alter brain development leading to structural anomalies that underly stuttering.

This suggests we should change the genetic diagnostic protocol for some people who stutter to include brain imaging studies.

The study also opens up further research into this new chaperone pathway, and related pathways, which will continue to improve our understanding of the genetic architecture of persistent developmental stuttering.

From the Spring 2024 Magazine

Podcast

Podcast Sign Up

Sign Up Virtual Learning

Virtual Learning Online CEUs

Online CEUs Streaming Video Library

Streaming Video Library